Or at least that’s the conclusion drawn by authors of a recent study that was published in Biological Psychiatry. Apfel et al. did a structural MRI study of 244 Gulf War vets and controls and compared the size of the hippocampus across subjects, and concluded that only current symptoms of PTSD appeared to be associated with it. Since the journal put out a press release about it, I figured there was something unique or novel about the study and decided to look into it.

The authors assessed lifetime and current symptoms of PTSD, in addition to a whole bunch of other variables such as such as alcohol use, depression, etc in a large sample of Gulf War vets. They then talk about the MRI part of the study, measuring pixels, and so on, and then provide the following figure (see below) – I am not sure why since all it really does is show where the hippocampus is. And if you are interested in this line of work, you probably already know that. It reminded me of stars making cameos in movies – interesting and attention-grabbing, but generally somewhat purposeless.

Anyway, onto the results, where the authors throw in all these variables in a massive regression to predict hippocampus volume (corrected for intracranial volume), and then show that only current PTSD symptom scores were a significant predictor. However, the amount of variance accounted for in hippocampal volume was not exactly stunning – an adjusted R2 of 2.6%.

This next part is what had me scratching my head. So far the authors worked with just symptom scores. But, at this point, they split up their sample into groups based on trauma and PTSD diagnoses – so you get:

1.) a group with no trauma (and by definition, no PTSD),

2.) a group exposed to trauma, but no PTSD,

3.) a group with lifetime, but no current PTSD (what they call remitted), and

4.) a group with both lifetime and current PTSD (called chronic).

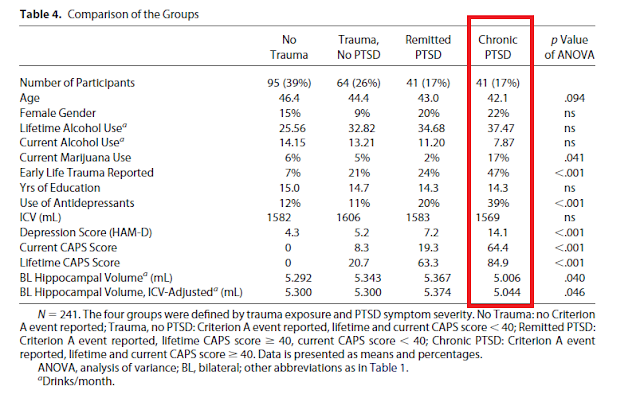

Notice what’s missing here – a group with current PTSD alone (in fact, only 3 people in the sample had current PTSD alone but they dropped them from the analyses!). And as you would expect, the chronic group had the highest rates of almost everything – the highest levels of trauma, highest lifetime AND current PTSD symptoms, highest rates of antidepressant use, etc. I have highlighted this column in red in the table from their paper below.

Next, they compare hippocampal sizes among groups using an ANOVA (as far as I can tell, without controlling for anything else) and show that the mean hippocampus volume of the chronic group is significantly smaller than that of the remitted group by 6.5% and that of the subjects with no PTSD by 5.1%. Still with me so far?

They then conclude that the size of the hippocampus is only affected by current PTSD symptoms and not by lifetime symptoms…..Here’s where they lost me. I am not sure I see the rationale for this conclusion. If they had done a regression with the lifetime and current symptoms of PTSD predicting hippocampal volume only in the chronic group, or had they even had a current PTSD only group with smaller hippocampal volumes, their conclusion would seem supported. However, since their analyses using current PTSD symptoms and their analyses using chronicity were done separately, their conclusion seems somewhat premature.

In other words, their measure of chronic PTSD is confounded with current and lifetime symptoms of PTSD, and doesn't really support what they are saying. Further, a basic pubmed search revealed several prior studies on hippocampal size in disorders such as PTSD and depression (with quite a few conflicting results). So they are not exactly breaking new ground here either. And reductions in size of 6.5% and 5.1% are not exactly earth-shattering. Which leaves me pretty puzzled as to why a press release was attached to this article....

Apfel BA, Ross J, Hlavin J, Meyerhoff DJ, Metzler TJ, Marmar CR, Weiner MW, Schuff N, & Neylan TC (2011). Hippocampal volume differences in gulf war veterans with current versus lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Biological psychiatry, 69 (6), 541-8 PMID: 21094937